Food Justice in Charlottesville, Virginia:

Taking Care of the Planet, Respecting People, and Ensuring Sustainable Profit

Elise Brenner

PLAC 5500

May 7, 2013

Each bite of food we take casts a vote. When you choose to bite in to an

apple, you aren’t just making a healthy snack choice. You are voting, with your

taste buds, with your wallet, and with your mind to support a certain way of life

that is dictated by our food system. You are deciding whether or not a farm

worker can pay for an injury he incurred picking your apple or if he can eat a

warm meal that night. You are deciding to support an institution that might create

major environmental problems for your area. And you are probably consuming a

number of chemicals which may do harm to your body. But the end problem is

the same: you have to eat.

The concept of food justice is one way we can begin to make sense of all

of the complicated factors that affect each bite of food we take. Food justice

takes in to account every player in our food system. From picker to producer,

from planter to procurement officer, and every step in between, food justice is a

comprehensive lens for viewing the issues that surround our food. Food justice is

a movement that is riding on the coattails of the organic and local food

movements–but some may argue it is casting a wider net. Food justice seeks to

invite everyone from sweet pea picker to the President of Monsanto to the

metaphorical dinner table of society.

The discussions food justice seeks to spur can be uncomfortable and

complicated but also fruitful and undeniably important in the recreation and

reclamation of society’s food systems: a revamping that takes in to account not

only the affordability, accessibility, and nutritional content of our food but also all

the people and processes involved in getting food from the fields (or the shelves,

or the kitchens) to our mouths.

The concept of food justice can seem overwhelmingly complex and to a

certain extent why shouldn’t it be? Taking a bite of your sandwich, picking an

apple off the pile at the grocery store, or choosing one restaurant over another

can seem like mindless activities. Our lives depend on eating so it seems natural

for there to be concern about what we are eating, where it comes from, and who

might be harmed by our consumption. In an ideal world, healthy food would be

available to all while not harming the environment or the people involved in any

step from getting food to our plates. Achieving food justice would mean to fulfill

the ultimate triple bottom line: taking care of the planet on which we grow our

food, respecting the people involved in getting food from farms to our tables, and

ensuring the sustainable profits that makes it all possible.

What does food justice mean for Charlottesville?

In order to discuss what food justice means for the city of Charlottesville, it

is first important to zoom out and take a brief moment to describe some of the

key issues related to Virginia’s agricultural economy. By doing this it may be

possible to point out larger gaps that will need to be filled in order to achieve food

justice in the city.

Virginia’s food system is inextricably linked to the agricultural industry of

the state. The 2011 Virginia Farm to Table Team reports the following statistics:

Virginia agriculture brings in $55 billion each year which supports 357,00 jobs.

Each job created by the agricultural and forestry industries supports another 1.5

jobs (Virginia Farm to Table Team 1). As concerned citizens continue to push

back against the industrial food system and seek to support local farmers and

local food businesses, it is an important time for the city of Charlottesville to

consider how it can make the most of this lucrative opportunity. While there are

no farming operations located within city limits, the city of Charlottesville is not

going to be a major player in contributing to the $2.9 billion of Virginia’s direct

agricultural output. However, the city most definitely has a place in growing the

state’s $26 billion agriculture-related business output. So what do all these

numbers have to do with food justice in Charlottesville?

Strengthening our food system by tapping in to the growth of the

agriculture-related business sector at the local level can improve food access,

affordability, and economic well-being for the city of Charlottesville. Within the

city, there are neighborhoods characterized by abounding wealth directly

adjacent with areas of extreme poverty. The disparate economic realities faced

by residents living in the city has been defined by Ridge Schuyler and Meg

Hannan’s 2011 repot for the Orange Dot Project entitled, “A Declaration of

Independence: Family Self-Sufficiency in Charlottesville”. According to the report,

1,388 or one out of five families in Charlottesville currently do not earn wages

they can survive on: they cannot adequately pay for food, clothing, shelter and

utilities (Hannan and Schulyer 4).

The findings of the report are hugely important in understanding that many

families in Charlottesville are financially stable enough to afford food (healthy

food that is sometimes very expensive) but many others are not. Additionally,

2,069 families living in the city do not earn enough money to be considered selfsufficient.

Food justice calls for families to be able to thrive, not just survive. The

Orange Dot Report calls for the community to “implement an economic

development strategy that will generate $20-30 million in additional total annual

income for these families.” The purpose of this paper will be to discuss

suggestions for how the food justice movement uncovers solutions to filling this

demonstrated financial gap and how the city of Charlottesville can harness the

power of local agriculture in doing so.

What do we already know about Charlottesville’s food system?

In the spring of 2006, the Department of Urban and Environmental

Planning at the University of Virginia began offering Planning Applications

Courses (PLAC) in food systems planning. Each course has offered students the

chance to explore a specific issue involving food through the academic discipline

of community planning for the city of Charlottesville and the surrounding counties

of Albemarle, Fluvanna, Greene, Louisa, and Nelson.

While the areas of study have been wildly different, many of the

recommendations for strengthening Charlottesville’s food system have been the

same. The work generated by these courses has identified major assets and

challenges to the city’s food system. It is time to address these challenges in the

name of food justice.

Beginning seven years ago, the first class presented a preliminary

assessment of Charlottesville’s regional food system. They identified the

following barrier: “Farmers have a lack of access to processing facilities and

therefore reduced opportunities to sell value-added products with longer shelf

lives” (PLAC 569, 37). In 2007, a team of students found that the biggest problem

“lies within the economy of the middle, where both processing and distribution

make up the missing link to ensuring a connected and unified local food system”

(Camburnbeck and Evans 1).

Food Processing was again identified as a barrier to the success of

Charlottesville’s local food system by the 2008 class. Their report included a

focus on the issue of meat processing for small farmers but also discussed the

concept of food miles in relation to food processing. Their report features the

Jefferson Area Board for Aging (JABA) as a case study; they concluded that “ a

local processing plant would be extremely helpful for JABA and would enable

them to serve local food to their clients during off-peak harvest seasons”

(“Healthy Communities” 123). The 2010 food policy audit looked at support for a

local food processing infrastructure and noted that at the time the proposed

community kitchen at the Jefferson school was the only processing option for the

city. While this has come to fruition, it does not feature the specialized equipment

needed for larger scale processing (Boswell et al. 4). Lastly, the work done by

one student in 2012 Food Heritage class reported on the connection between

healthful, minimally processed foods and the connection to the history. She found

that “strengthening small, local, healthy food processing and canning will

enhance our food heritage and our heritage as small businesspeople” (Kresse-

Smith 14)

The call for a food processing facility for the city of Charlottesville has

been made, but the city has not yet answered. Now is the time to consider some

very specific ways in which local food business entrepreneurs can team up with

the city to build a facility.

Food Justice Audit: Methodology and Community Engagement

During the spring semester of 2013, I participated in a community food

system course on food justice. Working off the foundation built upon the

previously mentioned courses, this class worked through the concept of food

justice as another way to measure the strength of Charlottesville’s food system.

By separating in teams, our class tested a newly conceived food justice

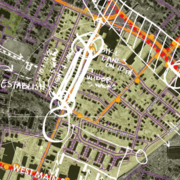

audit for the Charlottesville’s neighborhoods of 10th and Page, Belmont, Fifeville,

and Ridge Street. My team was tasked with the 10th and Page neighborhood,

The audit was separated in to “higher order” questions that addressed the whole

city and specific neighborhood questions. For the neighborhood questions, I took

on the Public Health and Food-Based Economic Development sections and

Danielle completed the Food Access & Infrastructure; School-Based Food &

Nutrition sections.

The 10th and Page neighborhood is about 80 acres large, it’s northern

boundaries are Preston Avenue and Grady Avenue, to the east is the Southern

Railroad, to the west is the CSX Railroad, and it’s western boundaries

include12th, 10th, and 11th streets (“10th and Page”). To become immersed in the

neighborhood and to fulfill the community engagement portion of the course, we

were placed with the Jefferson Area Board for Aging at the Mary Williams

Community Center located within the Jefferson School.

The strengths for food justice found in the neighborhood included the

availability of health care services—such as the Starr Hill Health Center (located

in the Jefferson School), access to a full service grocery store, and close

proximity to recreational parks. The major challenges preventing the fulfillment of

food justice in the neighborhood are a community recognized disconnect with the

Jefferson School, limited walk-ability of the neighborhood (due to narrow

sidewalks, fast through traffic, and inadequate lighting), and a lack of education

around proper nutrition for citizens of all ages living in the 10th and Page

neighborhood.

Our work at the Mary Williams Community Center can only be described

as thoroughly enjoyable and provided interesting insights to how JABA is

procuring food justice for the elderly community within the city of Charlottesville

and the surrounding counties. One of the first things we came to realize was that

the seniors attending the center were not from the 10th and Page neighborhood.

It soon became a reality that the focus of our study about food justice would be

around JABA and Charlottesville’s elderly population. During our sessions, the

most helpful thing we did was to serve lunch to the seniors. After noticing how

meals changed from day to day, especially with regards to the availability of fresh

fruits and vegetables versus canned goods, I decided that I wanted to find out

more about the stakeholder chain involved in getting a hot meal on the table at

the Mary Williams Community Center.

Thought Leader and Life History Interviews

To learn more about the services offered by JABA and the Mary Williams

Community Center I began my series of interviews with Cheryl Petencin, the

registered nurse and diabetes educator on site at the center. On February 21,

2013, Danielle and I interviewed Ms. Petencin in her office at the Mary Williams

Community Center.

Ms. Petencin has spent 30 years in community health and nursing, giving

her an interesting perspective on food justice. One of the biggest challenges of

her job is getting people to realize that they need to incorporate more fresh fruits

and vegetables in to their diets. Ms. Petencin remarked that canned food—a

form of food that is affordable and easy to eat for some out of society’s most

vulnerable populations (and often the form of food provided by food banks)—is

extremely high in sodium. She said, “people come to me and say they cannot

use those foods anymore because their doctors told them they have kidney

disease and they are at risk for going on dialysis and they cannot consume that

kind of food.” She went on to say that if there was the availability of lower

sodium canned and frozen that would be a great step in improving food

justice. In regards to meals at the center, she also explained, “Whenever there is

the availability of fresh fruits and vegetables, our clients are very excited about it.”

She understood food justice as having the “access to good quality,

minimally processed, nutritious food, and the ability to obtain factual information

as opposed to the current marketing strategies which enable our country to be in

the midst of an obesity epidemic.”

I also interviewed Emily Daidone, Manager of Community Centers and

Home Delivered Meal Program on April 8, 2013 in her office at the at the

Jefferson Area Board for Aging headquarters in Charlottesville. JABA’s

commitment to local food and food justice (not only for the elderly but also for the

community) is outstanding. After speaking with Emily Daidone I got a better

understanding of how complicated it is to fund these meals I helped serve during

my volunteer work at the Mary Williams Community Center.

Title III of the Older Americans Act provides funding to help state agencies

on aging provide both congregate and home-delivered meals for people 60 and

older. According to a report by Kristen J. Collelo, a specialist in health and aging

policy these meal services are “designed to address problems of food insecurity,

promote socialization, and promote the health and well-being of older persons”

(1). For JABA, the funding provided under Title III is channeled through the

Virginia Department for Aging and Rehabilitative Services (DARS). DARS

provides a set of nutrition guidelines the meals served by JABA must meet if they

are to receive the government funding. But the funding does not always cover the

entire cost of the meal. As Ms. Daidone noted in our interview, “the food we

get to follow those guidelines can be improved.” She also explained that the

biggest obstacle in providing healthful meals to the seniors is the cost and being

able to afford the best food available.

To broaden my focus back to the Charlottesville community, I interviewed

a local grocery store owner (who preferred not to be named in this report) on

March 22, 2013 at the store. This store is notable because it is located adjacent

to some of Charlottesville’s poorer neighborhood and because it is one of the

only independently owned grocery stores left in the area.

While the store does try to source locally, the interviewee explained that

price is the driving factor that enables the store to carry a product. The

interviewee said, “people like local, but local is expensive because the small

farmer has different expenses than a larger farmer has.” The store does offer

local produce and other local products when it can, but a lot of the times

customers find that cheaper items are of the same high quality as the local items

A longer, more in depth life history interview was also conducted with Mr.

Bobby Green at his home on March 5, 2013. Mr. Green is a retired Police

Community Service Officer and active community member who has devoted his

life to keeping the citizens of Charlottesville safe and fed. Mr. Green provided

some insight to the issues with food assistance program as he described SNAP

abuses within the city of Charlottesville. In his opinion, food assistance programs

like SNAP can be taken advantage of. He stressed the importance of making

sure government dollars, specifically regarding food assistance programs, get

spent on those who really need help the most

Case studies

Below are two case studies that may act as examples for Charlottesville.

They utilize similar models for establishing small to mid scale food processing

facilities. It will be important to consider the success and challenges faced by

other cities before moving forward in Charlottesville.

The Western Massachusetts Food Processing Center, located in

Greenfield Massachusetts, is owned by the Franklin County Community

Development Corporation. The center’s mission is to “promote economic

development through entrepreneurship, provide opportunities for sustaining local

agriculture, and promote best practices for food producers” (Western

Massachusetts Food Processing Center). Starting as a commercial kitchen, the

center has expanded to have blanching and freezing capabilities.

There are many aspects of the center that can be applied to

Charlottesville. The “Extend the Season” program was launched in 2009 and

aimed to increase the region’s accessibility to local food all year long through

canning and freezing which are known as “light processing.” The next step of the

program is called the “Extend the Season Farm to Institution Program.” The

mission of this program is to improve the value chain for both frozen and canned

products by selling frozen local food to institutions such as schools and hospitals.

________________________________________________________________

Leslie Schaller is the co-founder and Director of Programming of ACEnet,

located in Athens, Ohio. The mission of ACEnet is “to build networks, support

innovation, and facilitate collaboration with Appalachian Ohio’s businesses to

create a strong, sustainable regional economy” (ACEnet). ACEnet operates as a

business incubator and also owns the Food Manufacturing and Commercial

Kitchen Facility.

ACEnet improves the links in the regional food system value chain. By

operating a processing facility, farmers can sell more of their products to local

entrepreneurs seeking to create value-added products. The facility has also

helped farmers connect with restaurant owners they might not normally be able

to network with.

In connecting farmers to the buying power of larger institutions, Leslie

Schaller said, “If we can figure out how to take the bounty of fresh produce that is

grown in this region and extend the season through flash freezing, that’s a big

plus.” She went on to explain, “Now with some of the Institutional buyers and

restaurant buyers being interested in buying frozen food, especially in a food

service quantity packaging, we feel that it is a real opportunity for us at ACEnet to

generate new tenants, diversify our revenue streams, and then really meet all the

needs within the value chain” (ACEnet).

ACEnet’s recognizes the importance of creating a space for local

entrepreneurs to network while also operating a useful processing facility. Both

pieces are needed in order support the economic viability of the regional food

system. This example is especially important for Charlottesville because the

center not only offers the equipment necessary it also provides business training,

raises community awareness, and builds relationships to strengthen the food

system.

Community Based Ideas For Advancing Food Justice

In places where food is produced, improving local and regional food

systems is a way towards community development that builds health, wealth,

connection and capacity (Meter). Around 40% of all produce grown is sold below

cost or wasted all together (Gunders 4, IDA 27). The ability to preserve or

process produce that can’t be sold in the marketplace means the ability to use

goods that would be wasted and to make value added goods (like sauces, jams,

and salsas). Processing centers can include shared kitchens, dehydration

equipment, and freezing facilities. Entrepreneurs, local business people, city

officials, and concerned citizens should consider how the establishment of a food

processing facility could harness the power of our local agricultural economy.

The formation of Charlottesville’s Local Food Hub is one way our local

food system has been improved. The Local Food Hub functions as an aggregator

by connecting small farmers to wholesale markets. The next step in improving

our food system is to establish a food processing facility. A worker-owned food

processing facility in Charlottesville would be an efficient use of time, energy, and

funds that could help create meaningful employment for some of the city’s 1,388

families that currently do not make enough money to survive (Hannan and

Schuyler 4).

There are multiple community food processing projects currently on the

ground that could be scaled up, with support from the city. The Vinegar Hill

Canning Cooperative is a canning cooperative started by four female community

members. It was made possible the ingenuity of the founding members and

through partnerships with Market Central and the Jefferson Area Bureau on

Aging (JABA) and the sponsorship of the Healthy Food Coalition. They are

already working to can unsellable produce using the commercial kitchen facilities

at the Jefferson School and have begun selling their canned goods at

Charlottesville’s City Market. As explained by Joanie Freeman, “the cooperative

business model gives people an opportunity to enter in to the economic wealth

stream that exists Charlottesville.” The expansion of the canning cooperative

would be a win for food justice because it helps turn unsellable produce in to

profit, while also acknowledging the cultural importance of canning and the

history of Vinegar hill, and because the cooperative model respects the worker

by giving him or her ownership of the business.

The Jefferson Area Board for Aging has also called for the establishment

of a food processing center that could serve the city of Charlottesville and the

surrounding counties. JABA received funding to complete a feasibility study for

building a freezing facility in order to utilize products grown in Virginia for largescale

institutional meal service. With no known competitors in the area, JABA

found that this type of facility could generate sales between $3 and $5 million

(“Community Food System Project Phase III”). The study found that flash

freezing is the best type of processing for retaining the nutrition, taste, and

texture of produce. A flash freezing establishment would also be a win for food

justice because it has a lot of economic benefits: it creates a market for

unsellable produce, improves profits for farmers, creates jobs within the

agricultural business sector, and could encourage more local food businesses.

In either case, it would be possible to see how a processing facility would

be a win for the community, depending on where the funding comes from and

where it is built. Such a facility could be community or cooperative owned and

could include commercial kitchen, dehydration, freezing and canning equipment.

Possible next steps to take involve obtaining funding to build such an

establishment. One source of funding is the “Value-Added Producer Grants”

made available by the National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition. These grants

can be used to develop business plans, conduct feasibility studies, or otherwise

support businesses devoted to value-added products (“Value-Added Producer

Grants”).

Conclusions

One of the greatest strengths, the availability of both congregate and

home-delivered meals for seniors as provided by JABA, found through my

service work at the Mary Williams Center also pointed to the biggest gap and

room for the improvement for food justice in Charlottesville. By understanding

that JABA receives a bulk of their frozen food from a large food processing

facility in Florida, it became clear to me that food processing is a missing piece of

Charlottesville’s food system.

After reading through previous reports generated by the food systems

planning courses at the University of Virginia, I found that students, community

members, and agricultural leaders alike have been calling for food processing.

Additionally, I was able to run ideas about a food processing center by

community leader Joanie Freeman, Executive Director of the Healthy Food

Coalition and a founding member of the Vinegar Hill Canning Cooperative. Ms.

Freeman has been working tirelessly to raise money to establish a full-scale

cannery in Charlottesville as she believes this city needs a cannery. She

confirmed that there is a large market for second grade produce.

With the call for food processing coming from many different community

members around the city, I believe that the time has come to encourage the city

to aid in the establishment of a food processing facility to harness the total power

of our local agricultural economy. Additionally, as government funding for

programs like JABA’s meal service become limited, locally oriented business

solutions are necessary to protect the resilience of the city of Charlottesville.

Strengthening our food system by tapping in to the growth of agriculture-related

business through the establishment of a food processing facility at the local level

can fortify food justice by improving food access, affordability, and economic

well-being for the city of Charlottesville.

Works Cited

“10th and Page.” City of Charlottesville. Web. 17 Apr. 2013.

">http://www.charlottesville.org/Index.aspx?page=2046>.

ACEnet: The Appalachian Center for Economic Networks. Web. 24 Apr. 2013.

">http://www.acenetworks.org/>.

Bendfeldt, Eric, and Kenner Love. “Can Virginia Communities and Counties

Seize an Economic and Social Opportunity with Farm-Based Local and

Regional Economic Development?” Publications and Resources. Virginia

Cooperative Extension, 7 Oct. 2009. Web. 4 May 2012.

">http://pubs.ext.vt.edu/news/fbmu/2009/10/article_1.html>.

Boswell, Lauren, Fraiche, CoCo, and Janie Williams. “Charlottesville Community

Food System.” 7 May 2010. Web. 23 Apr. 2013.

http://www.virginia.edu/ien/docs/07FoodClassFINAL%20PAPERS/FINAL

%20REPORT_Charlottesville.pdf>.

Camburnbeck, Ella and Graham Evans. “The Missing Link: Distribution in

Charlottesville’s Local Food System.” 24 Apr. 2007.

http://www.virginia.edu/ien/docs/07FoodClassFINAL%20PAPERS/Distrib

ution.pdf>.

Colello, Kristen J. ”Older Americans Act: Title III Nutrition Services Program.”

Congressional Research Service. 1 Feb. 2010. Web. 13 Apr. 2013.

">http://www.aging.senate.gov/crs/nutrition1.pdf>.

“Community Food System Project Phase III.” Jefferson Area Board for Aging. 9

July 2012. Web. 25 Apr. 2013

http://www.ams.usda.gov/AMSv1.0/getfile?dDocName=STELPRDC5102

637>.

Freeman, Joanie. Personal Interview. 25 Apr. 2013.

Daidone, Emily. Personal Interview. 8 Apr. 2013.

Green, Bobby. Personal Interview. 5 Mar. 2013.

Gunders, Kara. “Wasted: How America is Losing up to 40 Percent of its Food

from

Farm to Fork to Landfill.” National Resources Defense Council. August

2012. Web. 22 April 2013. http://www.nrdc.org/food/files/wasted-food-

IP.pdf>.

Hannah, Meg and Ridge Schuyler. “A Declaration of Independence: Family Self-

Sufficiency in Charlottesville, Virginia.” 10 Sept. 2011. Web. 5 Apr. 2013.

http://pages.shanti.virginia.edu/ucare/files/2011/06/OrangeDotProjectCvil

lePoverty2011.pdf>.

“Health Communities, Healthy Food Systems (Part III): Global-Local Connections.

Spring 2008. Web. 24 Apr. 2013.

http://www.virginia.edu/ien/docs/07FoodClassFINAL%20PAPERS/Health

y%20Communities,%20Healthy%20Food%20Systems%20Part%20III%20

-%20Global-Local%20Connections%20Spring%202008%5B1%5D.pdf>.

Illinois Department of Agriculture (IDA). Illinois Department of

Commerce and Economic Opportunity. “Building Successful Food Hubs: A

Business Planning Guide for Aggregating and Processing Local Food in

Illinois.” January 2012. Web. 15 April 2013.

http://www.familyfarmed.org/wpcontent/

uploads/2012/01/IllinoisFoodHubGuide-final.pdf>.

Interviewee, Anonymous. Personal Interview. 22 Mar. 2013.

Kresse-Smith, Katelyn. “Food Processing in the State of Virginia: Cultivating

People and Industry.” 6 May 2012. Web. 24 Apr. 2013.

http://www.virginia.edu/ien/wpcontent/uploads/2012/02/Process_Katelyn

KresseSmith_CultivatingPeopleandIndustry.pdf>.

Meter, Ken. “Economic Leakage in Virginia’s Food Economy.” Local Farm and

Food Economy Studies. Crossroads Resource Center, 11 May 2007. Web.

28 Apr. 2012. ">http://www.crcworks.org/crcppts/va07.pdf>.

Petencin, Cheryl. Personal Interview. 21 Feb. 2013.

PLAC 569. “The Charlottesville Region Food System: A Preliminary

Assessment.” Spring 2006. Web. 17 Mar. 2013.

http://www.virginia.edu/ien/docs/07FoodClassFINAL%20PAPERS/06FIN

ALRept_Jun06_CvilleFood.pdf>.

“Value-Added Producer Grants.” National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition. Web.

15 April 2013.

http://sustainableagriculture.net/publications/grassrootsguide/local-foo...

rural-development/value-added-producer-grants/>.

Virginia Farm to Table Team. 2011. Virginia Farm to Table: Healthy Farms and

Healthy Food for the Common Wealth and Common Good. A Plan for

Strengthening Virginia’s Food System and Economic Future. E.S.

Bendfeldt, C. Tyler-Mackey, M. Benson, L. Hightower, K. Niewolny (Eds.)

December 2011.

Western Massachusetts Food Processing Center. Franklin County Development

Corporation. Web. 22 Apr. 2013. ">http://www.fccdc.org/fpcabout.html>.

Download the Food Justice in Charlottesville project here.